President John Dramani Mahama government’s decision to establish a framework for reviewing religious prophecies has sparked a heated public debate, cu

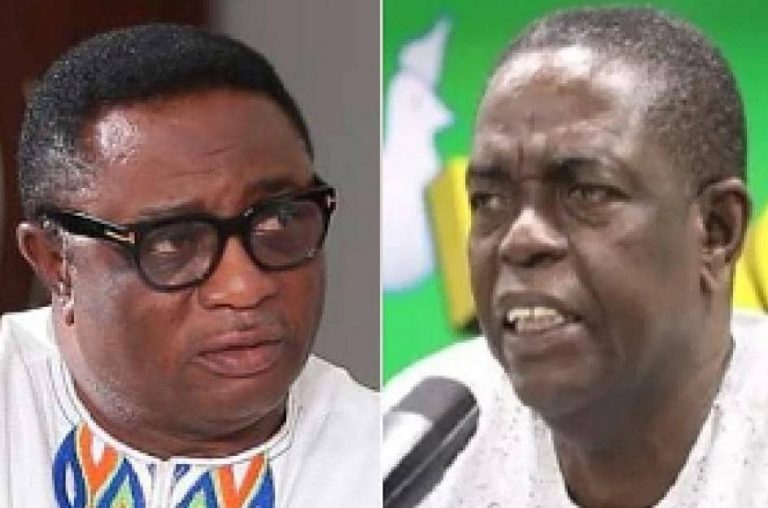

President John Dramani Mahama government’s decision to establish a framework for reviewing religious prophecies has sparked a heated public debate, culminating in a fiery exchange between veteran journalist Kwesi Pratt Jnr and Presidential Envoy for Interfaith and Ecumenical Relations, Elvis Afriyie Ankrah.

The controversy stems from a directive issued on August 10, 2025, encouraging religious leaders to submit prophecies of national concern—particularly those related to political leadership, governance, and national security—to the office of the Presidential Envoy.

The policy, government argues, is meant to differentiate credible spiritual revelations from fear-inducing predictions that could undermine public stability.

Elvis Afriyie Ankrah explained that the initiative seeks to prevent the misuse of religious platforms.

“We’re trying to curb a situation where people can say anything under the guise of prophecy without accountability. Even the Bible asks us to test the spirit,” he stated in a televised interview.

He emphasized that only prophecies with implications for national security fall under the directive, while others remain unaffected.

However, Kwesi Pratt, Managing Editor of The Insight newspaper, has been one of the fiercest critics of the move, calling it nothing but ‘nonsense.’

Speaking on Peace FM’s Kokrokoo morning show, Pratt dismissed the feasibility of such a policy, quipping: “Is he going to give God a call?”

His skepticism carried into a subsequent debate on Metro TV, where he pressed Afriyie Ankrah to explain the methodology for assessing spiritual claims.

“Elvis should show us how he’s going to review prophecy. What method is he going to use? How does Elvis believe that God will give somebody a prophecy and then refuse to show them how to communicate it?” Pratt asked, questioning both the practicality and legitimacy of the office’s role.

Afriyie Ankrah defended his position by citing scripture. “Do not despise prophecies, but test it all. 1 John 4:1-6 talks about testing the spirit.’

“There are competent, credible, proven men and women of God in this country. We work with all of them,” he argued, insisting that the measure is both biblical and necessary.

Since its announcement, the directive has triggered sharp public reactions. Memes mocking the office as a “Prophecy Clearance House” have circulated widely, with critics questioning the priorities at a time when the nation is grappling with economic pressures, unemployment, and a recent tragedy—the August 6 helicopter crash that claimed the lives of eight state officials.

Nonetheless, Elvis Afriyie Ankrah disclosed that more than 200 prophecies have already been submitted to his office, though he noted that 70–80% of them “have no substance.”

Only 2–5%, he said, merited further review, underscoring that the office is not merely a repository of prophecies but a bridge between government, faith communities, and international religious bodies such as the African Union and ECOWAS.

The debate also reflects a deeper historical tension in the governance: a secular state with strong religious undercurrents.

With over 90% of the population affiliated with a faith, religion plays a central role in public life—making the government’s move to regulate aspects of it both sensitive and contentious.

Kwesi Pratt has warned that Ghana may be the only democracy attempting to institutionalize prophecy reviews at the state level.

For him, the directive represents “nonsense” that risks trivializing governance.

Elvis Afriyie Ankrah, however, insists that it is a pragmatic step toward protecting national security from destabilizing pronouncements dressed as divine revelation.

COMMENTS